EPA Emerging Viral Pathogens and Hard Surface Disinfectants

At present, the virus responsible for COVID-19 is not on any EPA registered product lists, and therefore there is not a disinfectant which can make a specific claim to be effective against this new virus. However respiratory illnesses attributable to COVID-19 are caused by a coronavirus, and WAXIE can provide several broad-spectrum hard surface disinfectants that have been shown to be effective against other similar viruses, such as Human Coronavirus, SARS associated Coronavirus, Porcine Respiratory & Reproductive Syndrome Virus (PRRSV), and/or have been shown to be effective against viruses which are more difficult to inactivate such as Rotavirus, Rhinovirus Type 37, and Norovirus.

When used in accordance with the directions on the label for each associated product, these hard surface disinfectants have been shown to be effective against the virus (or viruses) referenced on the master label for that product. There are a number of disinfectant products which have already successfully gone through, or are in the process of going through, the protocol for the EPA Emerging Viral Pathogens Guidance for Antimicrobial Pesticides.1

List N: Disinfectants for Use Against SARS-CoV-2

On Thursday March 5, 2020, the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA)2 released a list of EPA-registered disinfectant products that have been qualified for use against SARS-CoV-2, the novel coronavirus responsible for COVID-19. Since the date of original publication, this list of disinfectant products has been updated several times, and the EPA has been publishing a revised list each week since mid-March which includes additional disinfectants which have been approved.

This list of disinfectant products, also referred to as List N: Disinfectants for Use Against SARS-CoV-2,3 includes products which have submitted data to EPA to show that they are effective against viruses which are harder to kill than SARS-CoV-2. The products on this initial list have been selected because they are amongst the first to be recognized by the EPA’s Emerging Viral Pathogens Guidance,4 or because they have demonstrated effectiveness against previous strains of coronavirus.

Why Emerging Viral Pathogen Guidance

The EPA developed and finalized this Emerging Viral Pathogen Guidance5 in 2016 as a result of growing public health concerns in the United States and globally about response to emerging pathogens, and the fact that pre-existing EPA-registered disinfectant product labels are not able to make any specific claims against a new and previously unidentified viral pathogen.

Because it is not possible to predict the occurrence of any particular emerging viral pathogen, and because any new pathogen is most likely unavailable for testing right away, few, if any EPA-registered disinfectant product labels have typically been able to specify use against a new category of infectious agents. And because testing the efficacy of an EPA-registered disinfectant against a new emerging pathogen can be difficult to accomplish in a timely manner, the Emerging Viral Pathogen Guidance was intended to allow for a more rapid response in the event of an outbreak.

The Emerging Viral Pathogen Guidance outlines a voluntary pre-approval process for making claims against emerging viral pathogens, and in the event of an outbreak, companies with pre-approved products can make off-label claims in technical literature, non-label-related websites, and social media.

Criteria for Disinfectants to Make Claims Against Emerging Viral Pathogens

In order to be eligible to be included on this list of disinfectants which can make claims against an emerging viral pathogen, the product should meet both of the following criteria:

- The product is an EPA-registered,6hospital/healthcare or broad-spectrum disinfectant with directions for use on hard, porous, or non-porous surfaces.

- The currently accepted product label (from an EPA registered product as described above in bullet point 1) should have disinfectant efficacy claims against at least one of the following viral pathogen groupings:

- A product should be approved by EPA to inactivate at least onelarge or one small non-enveloped virus to be eligible for use against an enveloped emerging viral pathogen.

- A product should be approved by EPA to inactivate at least onesmall, non-enveloped virus to be eligible for use against a large, non-enveloped emerging viral pathogen.

- A product should be approved by EPA to inactivate at least two small, non-enveloped viruses with each from a different viral family to be eligible for use against a small, non-enveloped emerging viral pathogen.

Viral Subgroup Classification

This approach which considers the viral subgroup classification was taken because the EPA and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) recognize that certain microorganisms can be ranked with respect to their tolerance to chemical disinfectants. The Spaulding Classification Model7 is used by CDC and it tiers microorganisms in accordance with the level of resistance to being killed (or inactivated) by typical disinfectant products. With this approach viruses are divided into three viral subgroups based on their relative resistance to inactivation. According to this hierarchy, if an antimicrobial product can kill a small, non-enveloped virus, it should be able to kill any large non-enveloped virus or any enveloped virus. Similarly, a product that can kill a large non-enveloped virus should be able to kill any enveloped virus. As described in the EPA Emerging Pathogen Guidance to Registrants,5 here is an overview of the three viral subgroups:

Small Non-Enveloped Viruses: these viruses can be highly resistant to inactivation by disinfectants. Despite the lack of a lipid envelope, these organisms have a very resistant protein capsid.

Large Non-Enveloped Viruses: these viruses are less resistant to inactivation than small non-enveloped viruses. Although they have a resistant protein capsid, their larger size makes them more vulnerable to inactivation than a small non-enveloped virus.

Enveloped Virus: these viruses are the least resistant to inactivation by disinfectants. The structure of these viruses includes a lipid envelope which is easily compromised by most disinfectants. Once the lipid envelope is damaged, the integrity of the virus is compromised, thereby neutralizing its infectivity.

As summarized in an article in Infection Control Today,8 the general idea of the EPA’s Emerging Viral Protection Guidance is that in order for a disinfectant to be considered effective against an emerging viral pathogen, it must demonstrate efficacy – in other words, have an EPA-approved claim – against viruses that are harder to kill than the specific emerging pathogen in question.

The SARS-CoV-2 virus which is responsible for COVID-19 is an enveloped virus and therefore it is the easiest virus to inactivate. An EPA-registered broad-spectrum hospital-grade disinfectant with a claim against at least one large non-enveloped virus or one small non-enveloped virus can be expected to be effective at inactivating an enveloped virus.

Selecting the Right Disinfectant Product

As referenced on the EPA website,3 the List N: Disinfectants for Use Against SARS-CoV-2 is not an exhaustive list of disinfectant products which can be used to inactivate the new strain of coronavirus, “there may be additional disinfectants that meet the criteria for use against SARS-CoV-2”, and the EPA is expediting review of submissions to identify additional disinfectant products which can potentially be used due to the outbreak of the novel coronavirus.21

WAXIE has several disinfectant products which meet the criteria to qualify for the emerging viral pathogen claim for an enveloped virus, and several have been submitted following EPA’s guidance for expedited emerging viral pathogens claim submissions.9 In addition, there are several products which have already successfully gone through the process, and are currently recognized on List N: Disinfectants for Use Against SARS-CoV-2.

Confirming A Disinfectant Product Is On The EPA List N

Just to reiterate, at this time there is not a product which can make a specific claim to be effective against SARS-CoV-2, the virus responsible for COVID-19. However, as referenced before the EPA has published a list of disinfectants,10 also known as List N: Disinfectants for Use Against SARS-CoV-2, which meet the EPA’s criteria for use against this new strain of coronavirus based upon the disinfectant product satisfying at least one of the following two criteria:

- The disinfectant product has an applicable Emerging Viral Pathogen claim

- The disinfectant product has a Human Coronavirus claim

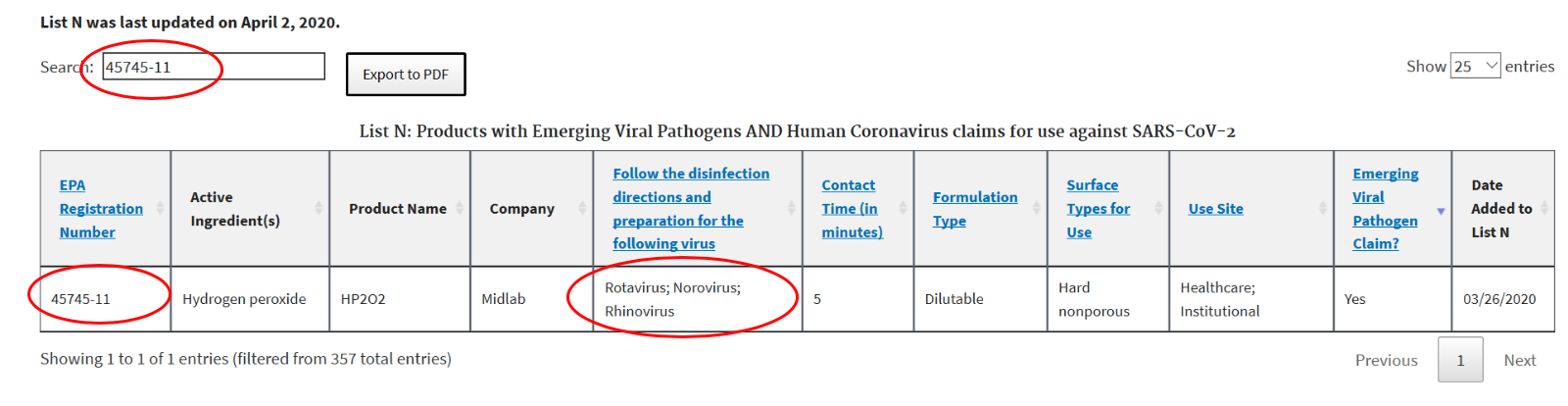

This List N has been a helpful resource to identify disinfectant products which can be used as part of a cleaning and disinfecting regimen to combat the current pandemic. However, if the list on the EPA website is searched using the product name only (for example “WAXIE HP Disinfectant Cleaner” or even just “WAXIE Disinfectant”), it may appear that the product you are looking for is not included on this list. This circumstance can be a potential source of confusion and alarm, but please be aware that the easiest way to find a product on the list is to enter the first two sets of its EPA registration number in the search bar on the webpage in order to confirm whether or not a specific disinfectant is in fact on the list.

The EPA has provided the following guidance for consumers searching on List N, “When purchasing a product, check if its EPA registration number is included on this list. If it is, you have a match and the product can be used against SARS-CoV-2. You can find this number on the product label – just look for the EPA Reg. No. These products may be marketed and sold under different brand names, but if they have the same EPA registration number, they are the same product.”10

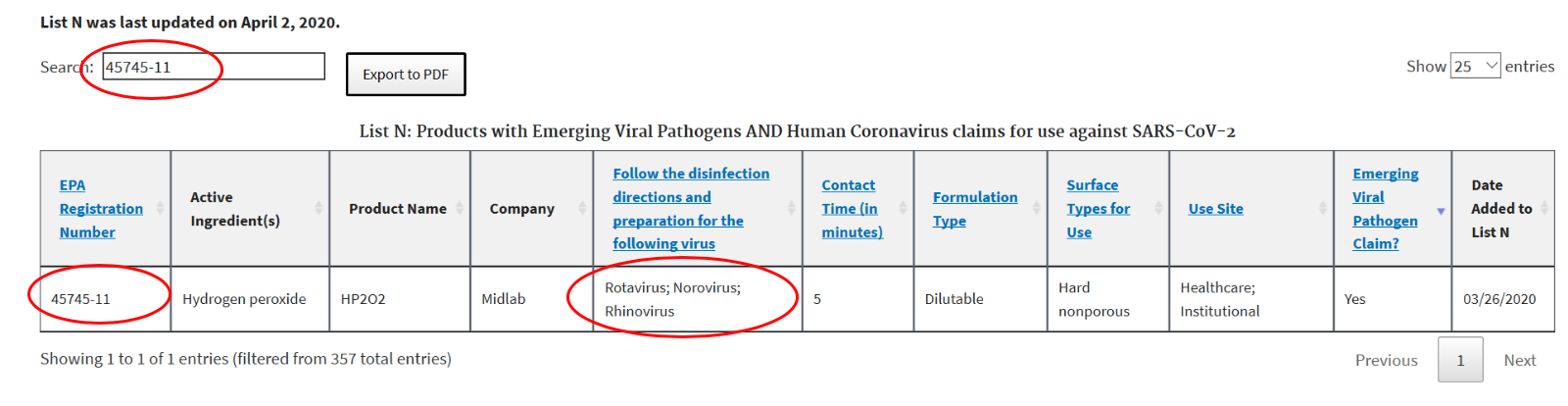

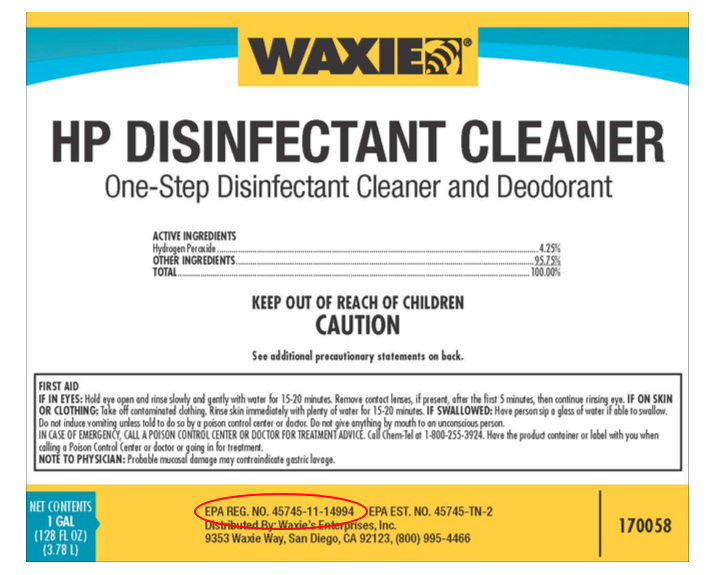

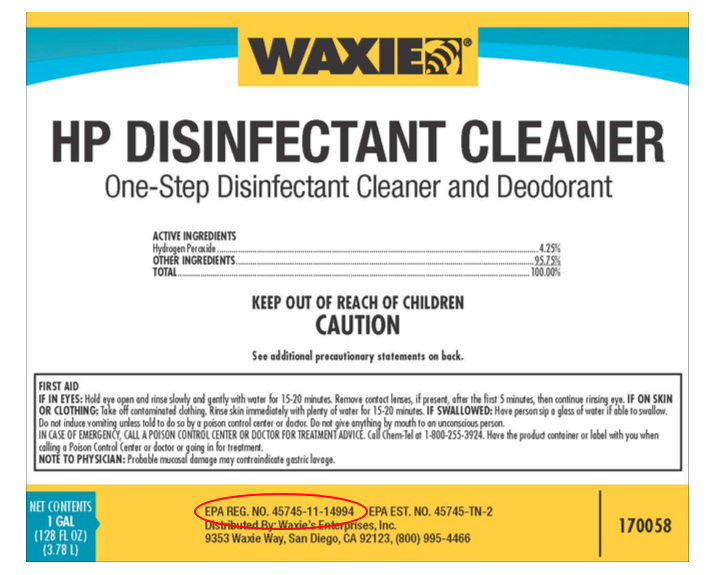

For example, the EPA Reg. No. for WAXIE HP Disinfectant Cleaner is “45745-11-14994”. Please see image below taken from EPA website displaying the search result for EPA Reg. No. “45745-11”, which is the first two sets of numbers in the EPA Reg. No. for this WAXIE brand product.

Please note that the “45745” in the EPA registration number is a reference to the company which provides the active ingredient used to make the disinfectant (in this case the active ingredient is “hydrogen peroxide”, and the company which makes this ingredient is “Midlab”), and the “11” is a reference to the specific product name or formula which is made using these raw materials (which Midlab calls “HP2O2”).

Other helpful information on this list on the EPA website includes guidance on what directions to follow when using the product – for example, for the WAXIE HP Disinfectant Cleaner, the applicable directions to use when trying to inactivate the SARS-CoV-2 virus would be the same directions on the master label to use to kill “Rotavirus; Norovirus; Rhinovirus”, with a recommended contact time of “5 minutes”.

Image: EPA Website, List N Search for WAXIE HP Disinfectant Cleaner

Reading A WAXIE Brand Disinfectant Product Label

For a list of WAXIE brand disinfectant products which are on EPA’s List N and their associated EPA registration numbers, please refer to COVID-19 Prevention Guide. Please note that the additional “14994” at the end of the first two sets of numbers of the EPA registration number for each WAXIE brand product is a reference to WAXIE’s sub-registration number for that particular product, and that in each instance the formula for the WAXIE brand product is the same as the formula for the master label which is included on the EPA List N.

To view this EPA registration number information on the WAXIE product label, please see example below for WAXIE HP Disinfectant Cleaner:

Image: WAXIE HP Disinfectant Label, WAXIE Item #170058

Please note that the EPA registration number for each disinfectant product is referenced on every label and secondary label for WAXIE brand disinfectant products, and this information may also be found when searching for each product in the WAXIE Product Catalog, as well as the WAXIE Online Catalog and the associated WAXIE Spec Sheets for each disinfectant.

In addition, your WAXIE Account Consultant or Chemical Specialist are also great resources to help answer any questions you may have regarding disinfectants, other cleaning chemicals, and hand hygiene.

Sources

- Environmental Protection Agency website, Guidance to Registrants: Process For Making Claims Against Emerging Viral Pathogens not on EPA-Registered Disinfectant Labels, updated July 31, 2017

- U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) website, News Releases – EPA Releases List of Disinfectants to Use Against COVID-19, reviewed March 5, 2020

- U.S. EPA website, Pesticide Registration – List N: Disinfectants for Use Against SARS-CoV-2, reviewed March 3, 2020

- U.S. EPA website, Pesticide Registration – Emerging Viral Pathogen Guidance for Antimicrobial Pesticides, reviewed March 3, 2020

- U.S. EPA website, Guidance To Registrants: Process For Making Claims Against Emerging Viral Pathogens No On EPA-Registered Disinfectant Labels, dated August 19, 2016

- U.S. EPA Regulations website, Product Performance Test Guidelines: OCSPP 810.2200 Disinfectants for Use on Hard Surfaces – Efficacy Data Recommendations [EPA 712-C-07-074], reviewed March 3, 2020

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) website, Infection Control – A Rational Approach to Disinfection and Sterilization, Guideline for Disinfection and Sterilization in Healthcare Facilities (2008), reviewed September 18, 2016

- Infection Control Today website article, Select Effective Disinfectants for Use Against the Coronavirus That Causes COVID-19, viewed February 26, 2020

- U.S. EPA website, News Releases, EPA Expediting Emerging Viral Pathogens Claim Submissions, reviewed March 9, 2020

- U.S. EPA website, Pesticide Registration – List N: Disinfectants for Use Against SARS-CoV-2, reviewed April 2, 2020